There is a moment in the life of an artist when he stops to look around, to take in and analyse his position in the ever changing modes of the art world. It is a moment of introspection, of questioning the underlying motives behind the need to present oneself to the world in this way. Why and to what purpose and where is the legitimacy of assuming this role?

It can be a difficult moment, often discouraging but it can also be a turning point, a time for reorientation. But as in the Grail Castle of the Arthurian legends, it is all a matter of posing the right question - whom does the Grail serve?

By 1992 I had been working for over 25 years with no or little feedback from the public, ignored by all aspects of the cultural scene; so I paused a while to try to understand what it was that drove me along such a lonely path that, to all intents and purposes, was leading me nowhere.

I started by observing my contemporaries, those artists who were fortunate enough to be integrated into the system of galleries and who, be it modestly, manage to make a living from their work. It was immediately evident that their talent lay as much in their ability to market themselves as in their artistic endeavours. Self marketing and working with the media is a notable part of art school training; a quality I sadly lack having, perhaps foolishly, abandoned college after my first year.

I then turned my attention to those artists appearing regularly in the media, the rock stars of the art world celebrated by public institutions and promoted by the most prestigious galleries on the international stage. Putting aside any judgement on the quality of their oeuvres, I was struck by the dominant cerebral quality of their work, so often reflecting the prevailing intellectual arrogance of post-modern times.

It was clear that public recognition for many of these artists was of paramount importance, their creative activities serving to nourish over-large egos, scaling their art as one would a pedestal with the unique objective of being admired from afar. Was it for this, for the admiration of others that I had been striving to achieve for all these years? Was art nothing but vanity? It became evident that, if I was to continue along this lonely path, I must look beyond the hollow reality that so frequently prevails in today's art.

By looking back at the role of the artist through history I hoped to find a more acceptable motive for my persevering in this direction. It is immediately noticeable that the further we go back through art history; the role played by the artist loses progressively its egotistic nature. Recent history shows the artist much as he is today but with an essential difference: he is working for the rich merchants or he is in the service of the aristocracy and it is these wealthy patrons that he is putting on a pedestal, not as yet himself. Further back still he is the vassal of the Church engaged in asserting the authority of Rome on an illiterate population but he has also an additional mission; that of purveying a spiritual message.

And then we come to what appears to be the end of art history, as though a wall has been erected to protect us from some unnameable danger.

It became clear that art history deals almost exclusively with the Christian era and that beyond the wall lies a mysterious otherworld that for some reason was seen as a threat to the Christian Church. Throughout Europe Christianity was imposed by the sword by an expanding Roman empire, driving the 'wild' Celtic tribes into the far reaching corners of the land and in some cases actually building walls to keep them at bay as with Hadrian's Wall in Northumberland. By exchanging a pantheon of gods and goddesses representing the many aspects of nature for one jealous God who, contrary to their pagan ancestors, gave Man dominion over all things including nature itself and in so doing shifting the consciousness of Man, alienating him from the natural world. The consequences of this monumental change in mentality have resulted in the catastrophic situation of the planet today. It occurred to me that it might also be responsible for the slow degradation of the artist's role in society, leading to the shallowness of today's art.

The first thing that comes to mind when researching art forms in prehistoric times are the Palaeolithic cave paintings such as those found at Lascaux. Images such as these, painted over 17000 years ago, are often located in places that are reached only with great difficulty and they are nearly always to be found in total darkness which suggests that they were in no way intended as decoration but were destined to serve as ritual images for magical purposes. This would imply that the ancestors of the artist were shamans. If we assume this to be true we must suppose that art has to do with survival and that the artist is an intercessor between his tribe and their gods, between Man and nature.

Being of Scots/Irish descent, I felt naturally inclined to pick up the thread from these Palaeolithic shamans in the pre-Christian Celtic culture that was once spread over the entire continent and that has been miraculously preserved in the far reaching corners of Europe where Christianity arrived at a later date and in a more gentle fashion and where many pagan traditions were eventually absorbed into and preserved by the Celtic Church.

Whilst researching evidence of shamanic practice in Celtic culture, I stumbled upon Robert Graves' book 'The White Goddess,' an extremely dense and scholarly study of Celtic mythology in which the author attempts to dissect and analyse what is perhaps one of the oldest texts to have come down to us: the Song of Amergin. Taken from the Irish Book of Invasions, it was first written down in the early medieval period but originally it was believed to have been sung by to the bard Amergin of the Milesians as he set foot on Irish soil in 1268 BCE. It is an epic poem, a magical invocation of nature, where each phrase, word or even letter provoked a meaning for those instructed in the secret art. It was a time when knowledge was transmitted orally between the initiated, the teachings of the hermetic tradition being encoded within the signs of a symbolic language.

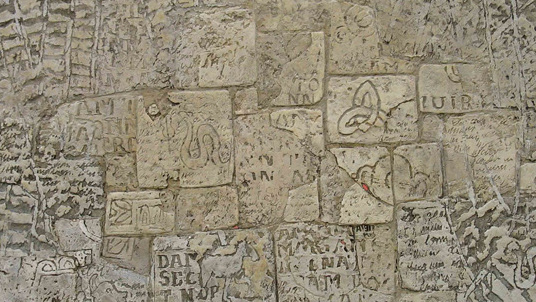

And so here with Amergin we have an illustration of an intercessor between Man and nature - an original artist. I felt that I should somehow involve this poem in my work in such a way that the conscious intention of this magical invocation of nature should, at all moments, be an integral part of the creative process. I decided that the substance of each and every painting would, from this time onwards, be created through the successive inscription (in the manner of palimpsests) of all or part of this poem as a kind of 'litany' - the object of this constant reiteration was not to give a legibility to the poem but rather, by consciously invoking its underlying quintessence throughout the entire creative process, to infuse the work with intent.

But for this intent to exist, to be more than just the result of a symbolic act, it became necessary for me, the artist, to Be what I was doing. Art is not about imitating, nor is it about appearances, art is born from the knowledge of what is; it is about Being. And so, quite naturally, this particular path that I had chosen in my quest for the meaning of art, prompted me to investigate the art of the Celtic poets with the result that for a number of years I became a student in a Druidic Order, training to be a Bard.

I do not pretend that this is the only way to apprehend the meaning of art. It is a personal interpretation that reveals more of the anxiety of being an artist than it answers the question of Art itself. All true artists attempt, at some time or another, to come to terms with their craft, to give meaning to their work and this can take many different forms. Some fail and pay the price; others go on to illustrate the human story through the ages, each one reflecting the shifting values of their time.

What I see as the shallowness of today's art is simply an illustration of the times in which we live. It does no more than express the lack of social cohesion and the heightened individualism of a society governed by market values. Artists who endorse these values through their artistic interventions, thus providing them with a cultural alibi, become quite naturally the chosen elite by the system they extol.

To set oneself aside from the dominant ideology of one's time by criticizing a system and its elected members, one takes the risk of being exiled from the cultural arena, of provoking the derision of ones contemporaries, of being accused of arrogance or stigmatized as a mystique. But it is the price that I must pay if I am to remain true to what I now believe to be the quintessence of my craft.

Ashley June 2009