What we feel when facing a work of art is an individual experience that is directly related to our capacity to receive the intentions of the artist and complete them within our own mental or emotional structure. A true work of art is an expression of the creation of the world and however contemporary and impenetrable it may appear to the layman, it should lend itself to a number of levels of perception so as to incite a response from the observer from within his or her own particular sphere of comprehension. Without going as far as Duchamp who declared that it is the onlooker who creates the work of art, we can at least say that it is by his unique interpretation of the work that the observer becomes its co-author.

The hermetic tradition for the transmission of knowledge on varying levels of consciousness worked in this way. The poetical invocations of the ancient Bards evoked simultaneously mystical meanings for the profane and magical knowledge for the initiated. Primitive writings were composed of signs evoking ideas. Both these means of transmitting knowledge had the advantage of obliging the receiver to think and to interpret the teachings buried within the words, using his own individual understanding of the hidden meanings enclosed within the signs of a symbolic language.

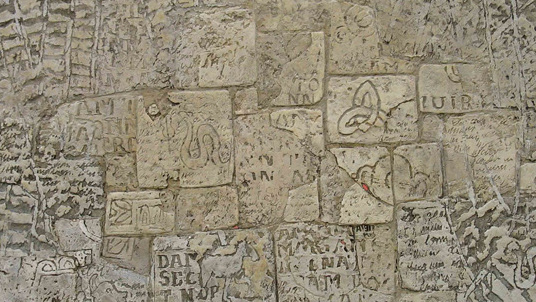

The imagery depicted in stone, found in churches and cathedrals, are the three dimensional equivalents of this hermetic language where the perceiver is called upon to decode the message at his own particular level of consciousness.

Teachings were transmitted in this way up until the end of the middle ages when symbolism was to gradually lose its esoteric significance, eventually depicting only its artistic and religious implications.

The hermetic tradition passed into the shadows safeguarded by alchemists, cabalists, secret societies and… artists. The artist who remains connected to the hidden order of art perpetrates this tradition intuitively through his work to this very day. By holding back that which may be completed by the onlooker, by suggesting rather than asserting his intentions; he encourages the spectator to contribute to the proposed work of art; his oeuvre being only half of the complete experience. In other words, a true work of art only becomes whole when we take it into ourselves.

The encounter can be subliminal occurring on an emotional plane or it can be a conscious intellectual experience as often happens when confronted with today’s contemporary art that conveys ideas and attitudes rather than feelings and which appeals to the conscious mind. But whatever form it takes and whatever the intention of the artist, the experience will be directly proportional to the onlookers level of perception, the work of art becoming the receptacle in which the hidden intentions of the artist and the acuity of the onlooker fuse together momentarily in a celebration of universal consciousness.